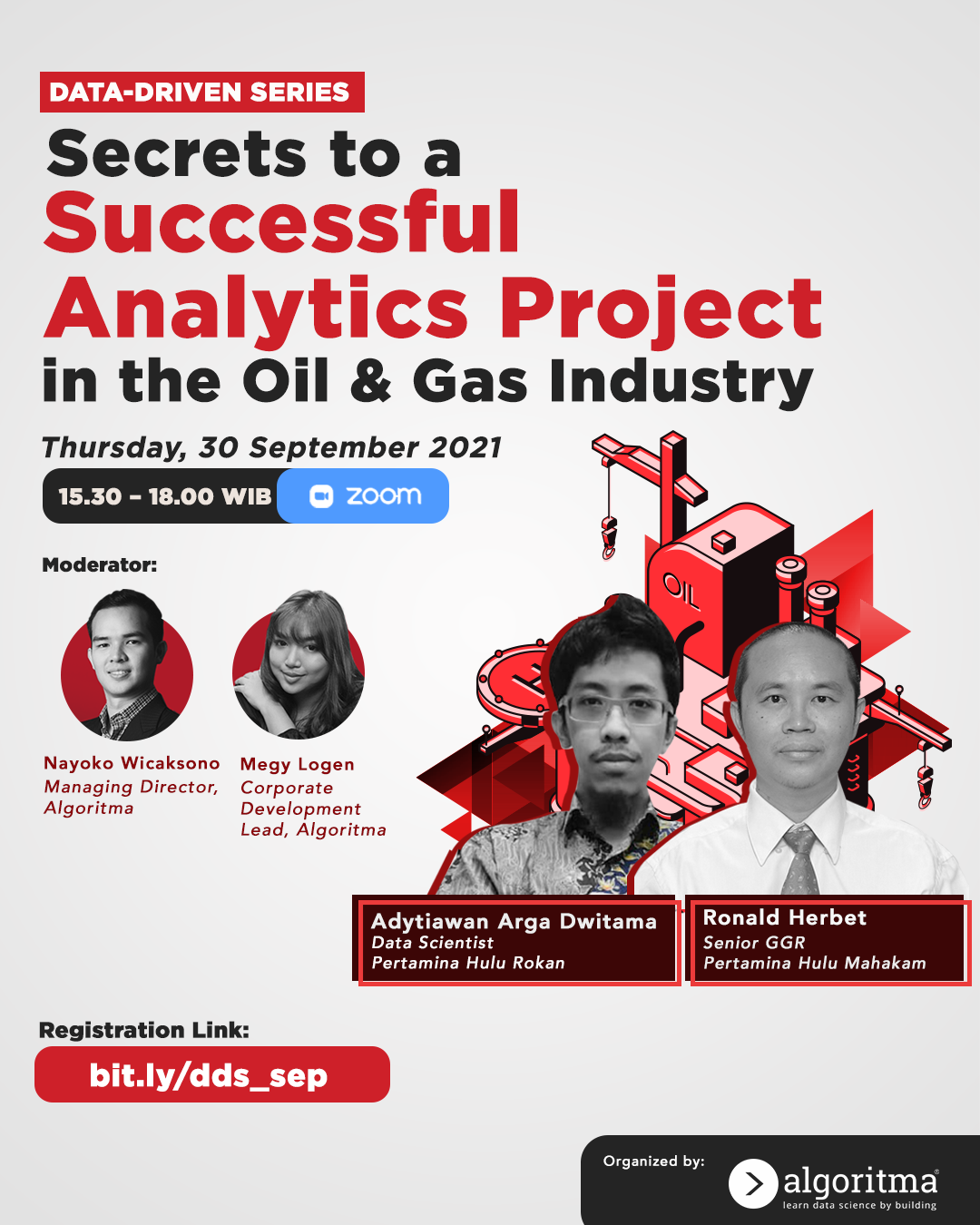

Overview

Regression analysis is a way that can be used to determine the relationship between the predictor variable (x) and the target variable (y).

Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) is the most common estimation method for linear models and it applies for good reasons. As long as your model meets the OLS assumptions for linear regression, you can rest easy knowing that you get the best estimate.

But in the real world to meet OLS regression assumptions will be very difficult. Especially the assumption of “Multicollinearity”. Multicollinearity assumptions occur when the predictor variables are highly correlated with each other and there are many predictors. This is reflected in the formula for variance given above: if m approaches n, the variance approaches infinity. When multicollinearity occurs, the OLS estimator will tend to have very large variants, although with small bias. However, estimators that have very large variants will produce poor estimates. This phenomenon is referred to as Overfitting.

This graphic illustrates (Figure 1) what bias and variance are. Imagine the bull’s-eye is the true population parameter that we are estimating, β, and the shots at it are the values of our estimates resulting from four different estimators - low bias and variance,

high bias and variance,

low bias and high variance,

high bias and low variance.

Figure 1: Bias and Variance (source: Shenoy, Aditi, 2019, What is Bias, Variance and Bias-Variance Tradeoff?)

Let’s say we have model which is very accurate, therefore the error of our model will be low, meaning a low bias and low variance as shown in first figure. All the data points fit within the bulls-eye.

Now how this bias and variance is balanced to have a perfect model? Take a look at the image below and try to understand.

Figure 2: Bias Variance Tradeoff (source: Hsieh, Ben, 2012, Understanding the Bias-Variance Tradeoff in k means clustering)

In the picture above, it can be seen based on the complexity of the model that has 2 possible errors, namely:

Underfitting

Overfitting

To overcome Underfitting or high bias, we can basically add new parameters to our model so that the model complexity increases, and thus reducing high bias.

As a complexity model, which in the case of linear regression can be considered as the number of predictors, it increases, the expected variance also increases, but the bias decreases. An impartial OLS will place us on the right side of the image, which is far from optimal, this term is called Overfitting.

Now, how can we overcome Overfitting for a regression model?

Basically there are two methods to overcome overfitting,

1. Reduce the model complexity,

To reduce the complexity of the model we can use stepwise Regression (forward or backward) selection for this, but that way we would not be able to tell anything about the removed variables’ effect on the response.

But we will introduce you to 2 Regularization Regression methods that are quite good and can be used to overcome overfitting obstacles.

2. Regularization.

Regularization

Regularization is a regression technique, which limits, regulates or shrinks the estimated coefficient towards zero. In other words, this technique does not encourage learning of more complex or flexible models, so as to avoid the risk of overfitting.

The formula for Multiple Linear Regression looks like this.

$$y = \beta_{0} + \beta_{i}x_{i}$$

Here Y represents the relationship studied and β represents the estimated coefficient for different variables or predictors (X).

The procedure for selecting a regression line uses an error value, known as Sum Square Error (SSE). Regression lines are formed when minimizing SSE values.

Where the SSE formula is as follows:

$$SSE =\sum_{x = 1}^{n} (y_{i}-\hat{y}_{i})^2$$

That’s why if I want to predict house prices based on land area, but I only have 2 data train like Figure 3a below,

Figure 3: OLS Regression

then the regression model (line) that I have is like figure 3.

But the problem is what if it turns out I have test data and its distribution is like the blue dot below?

Figure 4: Overfitting

Figure 4 above shows that if we have a regression line in orange, and want to predict test data like the blue dot above, the estimator has a very large variance even though it has a small bias value, and The regression model formed is very good for the data train but bad for the test data. When the phenomenon occurs, the model built is subject to overfitting problems.

There are two types of regression that are quite familiar and use this Regularization technique, namely:

Ridge Regression

Lasso Regression

Ridge Regression

Ridge Regression is a variation of linear regression. We use ridge regression to tackle the multicollinearity problem. Due to multicollinearity, we see a very large variance in the least square estimates of the model. So to reduce this variance a degree of bias is added to the regression estimates.

Ordinary Least Square (OLS) will create a model by minimizing the value of Sum Square Error (SSE), Whereas The Rigde regression will create a model by minimizing :

$$SSE + λ \sum_{i = 1}^{n} (\beta_{i})^2$$

Figure 5: Ridge Regression

It can be seen that the main idea of Ridge Regression is to add a little bias to reduce the value of the variance estimator.

It can be seen that the greater the value of λ (lambda) the regression line will be more horizontal, so the coefficient value approaches 0.

Figure 6: Lambda Parameter

If λ = 0, the output is similar to simple linear regression.

If λ = very large , the coefficients value approaches 0.

Lasso Regression

LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage Selector Operator), The algorithm is another variation of linear regression like ridge regression. We use lasso regression when we have large number of predictor variables.

The equation of LASSO is similar to ridge regression and looks like as given below.

$$SSE + λ \sum_{i = 1}^{n} |\beta_{i}|$$

Here the objective is as follows: If λ = 0, We get same coefficients as linear regression If λ = vary large, All coefficients are shriked towards zero.

The main difference between Ridge and LASSO Regression is that if ridge regression can shrink the coefficient close to 0 so that all predictor variables are retained. Whereas LASSO can shrink the coefficient to exactly 0 so that LASSO can select and discard the predictor variables that have the right coefficient of 0.

Ordinary Least Square (OLS) Regression

Libraries

The first thing to do is to prepare several libraries as below.

library(glmnet)

library(caret)

library(dplyr)

library(car)

library(nnet)

library(GGally)

library(lmtest)

Read Data

data(mtcars)

mtcars <- mtcars %>%

select(-vs, -am)

head(mtcars)

#> mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec gear carb

#> Mazda RX4 21.0 6 160 110 3.90 2.620 16.46 4 4

#> Mazda RX4 Wag 21.0 6 160 110 3.90 2.875 17.02 4 4

#> Datsun 710 22.8 4 108 93 3.85 2.320 18.61 4 1

#> Hornet 4 Drive 21.4 6 258 110 3.08 3.215 19.44 3 1

#> Hornet Sportabout 18.7 8 360 175 3.15 3.440 17.02 3 2

#> Valiant 18.1 6 225 105 2.76 3.460 20.22 3 1

Now we will try to create an OLS model using mtcars data, which consists of 32 observations (rows) and 11 variables:

[, 1] mpg Miles/(US) gallon

[, 2] cyl Number of cylinders

[, 3] disp Displacement (cu.in.)

[, 4] hp Gross horsepower

[, 5] drat Rear axle ratio

[, 6] wt Weight (1000 lbs)

[, 7] qsec 1⁄4 mile time

[, 8] gear Number of forward gears

[, 9] carb Number of carburetors

In this case, OLS Regression, Ridge Regression, and LASSO Regression will be applied to predict mpg based on 10 other predictor variables.

- Correlation

ggcorr(mtcars, label = T)

Data Partition

train <- head(mtcars,24)

test <- tail(mtcars,8)[,-1]

## Split Data for Ridge and LASSO model

xtrain <- model.matrix(mpg~., train)[,-1]

ytrain <- train$mpg

test2 <- tail(mtcars,8)

ytest <- tail(mtcars,8)[,1]

xtest <- model.matrix(mpg~., test2)[,-1]

OLS Regression Model

ols <- lm(mpg~., train)

summary(ols)

#>

#> Call:

#> lm(formula = mpg ~ ., data = train)

#>

#> Residuals:

#> Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

#> -4.3723 -1.1602 -0.1456 1.1948 4.1680

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

#> (Intercept) -5.42270 23.86133 -0.227 0.8233

#> cyl 0.69631 1.17331 0.593 0.5617

#> disp -0.00103 0.01909 -0.054 0.9577

#> hp -0.01034 0.03028 -0.342 0.7374

#> drat 5.36826 2.63249 2.039 0.0595 .

#> wt -0.47565 2.34992 -0.202 0.8423

#> qsec 0.01171 0.76250 0.015 0.9879

#> gear 3.44056 3.01636 1.141 0.2719

#> carb -2.66168 1.25748 -2.117 0.0514 .

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> Residual standard error: 2.553 on 15 degrees of freedom

#> Multiple R-squared: 0.8886, Adjusted R-squared: 0.8293

#> F-statistic: 14.96 on 8 and 15 DF, p-value: 0.000007346

Assumption Checking of OLS Regression Model

Linear regression is an analysis that assesses whether one or more predictor variables explain the dependent (criterion) variable. The regression has four key assumptions:

1. Linearity

linear regression needs the relationship between the predictor and target variables to be linear. To test this linearity you can use the cor.test () function.

H0 : Correlation is not significant

H1 : Correlation is Significant

cbind(cor.test(mtcars$mpg,mtcars$cyl)[[3]],

cor.test(mtcars$mpg,mtcars$disp)[[3]],

cor.test(mtcars$mpg,mtcars$hp)[[3]],

cor.test(mtcars$mpg,mtcars$drat)[[3]],

cor.test(mtcars$mpg,mtcars$wt)[[3]],

cor.test(mtcars$mpg,mtcars$qsec)[[3]],

cor.test(mtcars$mpg,mtcars$gear)[[3]],

cor.test(mtcars$mpg,mtcars$carb)[[3]])

#> [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

#> [1,] 0.0000000006112687 0.0000000009380327 0.0000001787835 0.0000177624

#> [,5] [,6] [,7] [,8]

#> [1,] 0.0000000001293959 0.01708199 0.005400948 0.001084446

From the p-values above shows each predictor variable has a significant correlation on the target variable (mpg).

2. Normalitas Residual

OLS Regression requires residuals from a standard normal distribution model. Why? because if the residuals have a normal standard distribution, then the residual distribution is spread around with mean 0 and some variance.

H0 : Residuals are normally distributed

H1 : Residuals are not normally distributed

shapiro.test(ols$residuals)

#>

#> Shapiro-Wilk normality test

#>

#> data: ols$residuals

#> W = 0.99087, p-value = 0.9979

Based on the above results obtained p-value (0.1709) > alpha (0.05) so that it was concluded that Residuals are normally distributed.

3. No Heteroskedasticity

The assumption of No Heteroskedasticity or No Homoskedasticity means that the residual model has a homogeneous variant, and does not form a pattern. The No Heteroskedasticity assumption can be tested using the bptest () function.

H0 : Distributed residuals are homogenous

H1 : Distributed residuals are heterogenous

bptest(ols)

#>

#> studentized Breusch-Pagan test

#>

#> data: ols

#> BP = 15.888, df = 8, p-value = 0.044

Based on the above results obtained p-value (0.0356) < alpha (0.05) so it can be concluded that resDistributed residuals are heterogenous

4. No Multicolinearity

Multicollinearity is a condition where there are at least 2 predictor variables that have a strong relationship. We expect that there is no multicollinearity. Multicollinearity is marked if the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) value is > 10.

vif(ols)

#> cyl disp hp drat wt qsec gear

#> 14.649665 19.745238 11.505313 7.234090 18.973493 5.619677 8.146065

#> carb

#> 8.646147

In the above output, there are 7 predictor variables that have a VIF value > 10. This indicates that the estimator model of the ols model has a large variance (Overfitting Problem).

Evidence of Overfitting

Let’s prove it by comparing the MSE (Mean Square Error) error value between the data train and the test data.

- Data Train

ols_pred <- predict(ols, newdata = train)

mean((ols_pred-ytrain)^2)

#> [1] 4.072081

- Data Test

ols_pred <- predict(ols, newdata = test)

mean((ols_pred-ytest)^2)

#> [1] 22.15188

As mentioned above, one way to overcome overfitting can be to reduce the dimensions using the Stepwise Regression method.

Stepwise regression is a combination of forwarding and backward methods, the first variable entered is the variable with the highest and significant correlation with the dependent variable, the second incoming variable is the variable with the highest and still significant correlation after certain variables enter the model then other variables that is in the model is evaluated, if there are variables that are not significant then the variable is excluded.

Stepwise Regression

names(mtcars)

#> [1] "mpg" "cyl" "disp" "hp" "drat" "wt" "qsec" "gear" "carb"

lm.all <- lm(mpg ~., train)

stepwise_mod <- step(lm.all, direction="backward")

#> Start: AIC=51.7

#> mpg ~ cyl + disp + hp + drat + wt + qsec + gear + carb

#>

#> Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC

#> - qsec 1 0.0015 97.731 49.700

#> - disp 1 0.0190 97.749 49.704

#> - wt 1 0.2669 97.997 49.765

#> - hp 1 0.7599 98.490 49.886

#> - cyl 1 2.2946 100.025 50.257

#> - gear 1 8.4767 106.207 51.696

#> <none> 97.730 51.700

#> - drat 1 27.0937 124.824 55.572

#> - carb 1 29.1906 126.921 55.972

#>

#> Step: AIC=49.7

#> mpg ~ cyl + disp + hp + drat + wt + gear + carb

#>

#> Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC

#> - disp 1 0.027 97.759 47.707

#> - wt 1 0.404 98.135 47.799

#> - hp 1 0.777 98.509 47.890

#> - cyl 1 2.675 100.406 48.348

#> <none> 97.731 49.700

#> - gear 1 8.500 106.231 49.702

#> - drat 1 27.092 124.824 53.572

#> - carb 1 33.987 131.719 54.863

#>

#> Step: AIC=47.71

#> mpg ~ cyl + hp + drat + wt + gear + carb

#>

#> Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC

#> - hp 1 1.001 98.759 45.951

#> - wt 1 1.127 98.886 45.982

#> - cyl 1 2.948 100.707 46.420

#> <none> 97.759 47.707

#> - gear 1 8.716 106.475 47.757

#> - drat 1 27.829 125.588 51.719

#> - carb 1 37.084 134.843 53.425

#>

#> Step: AIC=45.95

#> mpg ~ cyl + drat + wt + gear + carb

#>

#> Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC

#> - wt 1 2.052 100.811 44.445

#> - cyl 1 2.122 100.881 44.461

#> <none> 98.759 45.951

#> - gear 1 17.906 116.666 47.950

#> - drat 1 27.261 126.020 49.801

#> - carb 1 47.357 146.116 53.352

#>

#> Step: AIC=44.44

#> mpg ~ cyl + drat + gear + carb

#>

#> Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC

#> - cyl 1 3.846 104.66 43.343

#> <none> 100.81 44.445

#> - gear 1 23.549 124.36 47.483

#> - drat 1 59.197 160.01 53.532

#> - carb 1 115.220 216.03 60.737

#>

#> Step: AIC=43.34

#> mpg ~ drat + gear + carb

#>

#> Df Sum of Sq RSS AIC

#> <none> 104.66 43.343

#> - gear 1 21.151 125.81 45.761

#> - drat 1 57.478 162.14 51.849

#> - carb 1 259.357 364.01 71.259

summary(stepwise_mod)

#>

#> Call:

#> lm(formula = mpg ~ drat + gear + carb, data = train)

#>

#> Residuals:

#> Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

#> -4.8838 -1.4587 0.0255 1.2761 4.2824

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

#> (Intercept) -3.3923 3.6017 -0.942 0.35750

#> drat 5.2265 1.5770 3.314 0.00346 **

#> gear 3.4169 1.6996 2.010 0.05806 .

#> carb -2.7135 0.3854 -7.040 0.000000792 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> Residual standard error: 2.288 on 20 degrees of freedom

#> Multiple R-squared: 0.8808, Adjusted R-squared: 0.8629

#> F-statistic: 49.24 on 3 and 20 DF, p-value: 0.000000002032

vif(stepwise_mod)

#> drat gear carb

#> 3.232190 3.220083 1.011370

shapiro.test(stepwise_mod$residuals)

#>

#> Shapiro-Wilk normality test

#>

#> data: stepwise_mod$residuals

#> W = 0.98755, p-value = 0.9869

bptest(stepwise_mod)

#>

#> studentized Breusch-Pagan test

#>

#> data: stepwise_mod

#> BP = 7.1292, df = 3, p-value = 0.06789

Ridge Regression Model

As mentioned above, the second way to overcome the problem of overfitting in regression is to use Regularization Regression. Two types of regression regularization will be discussed this time, the first is Ridge regression.

Ridge regression is the same as OLS regression

Below, the writer tries to prove whether Ridge has parameters \(\lambda = 0\) then the Ridge regression coefficient is approximately the same as the Ordinary Least Square Regression coefficients.

ridge_cv <- glmnet(xtrain, ytrain, alpha = 0,lambda = 0)

predict.glmnet(ridge_cv, s = 0, type = 'coefficients')

#> 9 x 1 sparse Matrix of class "dgCMatrix"

#> 1

#> (Intercept) -5.105168916

#> cyl 0.675181160

#> disp -0.001095199

#> hp -0.009943070

#> drat 5.323214337

#> wt -0.475257511

#> qsec 0.004891085

#> gear 3.456626642

#> carb -2.660723992

ols$coefficients

#> (Intercept) cyl disp hp drat

#> -5.422701011 0.696306643 -0.001029893 -0.010342436 5.368257224

#> wt qsec gear carb

#> -0.475646420 0.011715279 3.440558813 -2.661675645

Choosing Optimal Lambda Value of Ridge Regression

As already discussed \(\lambda\) is an error value parameter used to add bias so that variance and estimator decrease.

The glmnet function trains the model multiple times for all the different values of lambda which we pass as a sequence of vector to the lambda = argument in the glmnet function.

set.seed(100)

lambdas_to_try <- 10^seq(-3, 7, length.out = 100)

The next task is to identify the optimal value of lambda which results into minimum error. This can be achieved automatically by using cv.glmnet() function. Setting alpha = 0 implements Ridge Regression.

set.seed(100)

ridge_cv <- cv.glmnet(xtrain, ytrain, alpha = 0, lambda = lambdas_to_try)

plot(ridge_cv)

From the picture above it shows the best log (lambda) between about 0 to 2.5 because it has the smallest MSE value. On the x-axis (above) you can see all the numbers are 8. This shows the number of predictors used. No matter how much lambda is used, the predictor variable remains 8. This means that Ridge Regression cannot perform automatic feature selection.

Extracting the Best Lambda of Ridge Regression

best_lambda_ridge <- ridge_cv$lambda.min

best_lambda_ridge

#> [1] 1.707353

Build Models Based on The Best Lambda

ridge_mod <- glmnet(xtrain, ytrain, alpha = 0, lambda = best_lambda_ridge)

predict.glmnet(ridge_mod, type = 'coefficients')

#> 9 x 1 sparse Matrix of class "dgCMatrix"

#> s0

#> (Intercept) 17.201163649

#> cyl -0.354685636

#> disp -0.004855094

#> hp -0.013125376

#> drat 2.377336631

#> wt -1.163291643

#> qsec 0.060788898

#> gear 1.415532975

#> carb -1.065339475

So the Ridge Regression model obtained is $$mpg = 17.81 - 0.39cyl -0.005disp-0.01hp+2.05drat-1.12wt+0.09qseq+1.32gear-0.90carb$$

LASSO Regression Model

Choosing Optimal Lambda Value of LASSO Regression

Setting the range of lambda values, with the same parameter settings as Ridge Regression

lambdas_to_try <- 10^seq(-3, 7, length.out = 100)

Identify the optimal value of lambda which results into minimum error. This can be achieved automatically by using cv.glmnet() function. Setting alpha = 1 implements LASSO Regression.

set.seed(100)

lasso_cv <- cv.glmnet(xtrain, ytrain, alpha = 1, lambda = lambdas_to_try)

plot(lasso_cv)

From the picture above it shows the best log(lambda) between about -1 to 0, because it has the smallest MSE value. On the x-axis (above) has a different value, based on the best lambda it can be seen that the best predictor variable is 5. This shows that LASSO Regression can perform automatic feature selection.

Extracting the est lambda of LASSO Regression

best_lambda_lasso <- lasso_cv$lambda.min

best_lambda_lasso

#> [1] 0.1668101

Build Models Based The Best Lambda

# Fit final model, get its sum of squared residuals and multiple R-squared

lasso_mod <- glmnet(xtrain, ytrain, alpha = 1, lambda = best_lambda_lasso)

predict.glmnet(lasso_mod, type = 'coefficients')

#> 9 x 1 sparse Matrix of class "dgCMatrix"

#> s0

#> (Intercept) 7.37367761

#> cyl .

#> disp .

#> hp -0.01044739

#> drat 4.12926425

#> wt -0.97081377

#> qsec .

#> gear 2.14674952

#> carb -1.88455227

From the results above it can be seen that the variables cyl, disp, and qseq have decreased coefficients to exactly 0. So the LASSO Regression model obtained is

$$mpg = 8.31-0.001hp+4.063drat-1.00wt+1.96gear-1.79carb$$

Model Comparison

Compare The MSE value of Data Train and Test

OLS Regression

# MSE of Data Train (OLS)

ols_pred <- predict(ols, newdata = train)

mean((ols_pred-ytrain)^2)

#> [1] 4.072081

# MSE of Data Test (OLS)

ols_pred <- predict(ols, newdata = test)

mean((ols_pred-ytest)^2)

#> [1] 22.15188

# MSE of Data Train (Stepwise)

back_pred <- predict(stepwise_mod, newdata = train)

mean((back_pred-ytrain)^2)

#> [1] 4.360721

# MSE of Data Test (Stepwise)

back_pred <- predict(stepwise_mod, newdata = test)

mean((back_pred-ytest)^2)

#> [1] 22.41245

# MSE of Data Train (Ridge)

ridge_pred <- predict(ridge_mod, newx = xtrain)

mean((ridge_pred-ytrain)^2)

#> [1] 4.920852

# MSE of Data Test (Ridge)

ridge_pred <- predict(ridge_mod, newx = xtest)

mean((ridge_pred-ytest)^2)

#> [1] 7.22441

# MSE of Data Train (LASSO)

lasso_pred <- predict(lasso_mod, newx = xtrain)

mean((lasso_pred-ytrain)^2)

#> [1] 4.269417

# MSE of Data Test (LASSO)

lasso_pred <- predict(lasso_mod, newx = xtest)

mean((lasso_pred-ytest)^2)

#> [1] 13.56875

Based on the above results the best regression model using mtcars data is Ridge Regression. Because the difference of MSE data training and testing is not much different.

Compare prediction results from all four models.

predict_value <- cbind(ytest, ols_pred, ridge_pred, lasso_pred,back_pred)

colnames(predict_value) <- c("y_actual", "ols_pred", "ridge_pred", "lasso_pred", "stepwise_pred")

predict_value

#> y_actual ols_pred ridge_pred lasso_pred stepwise_pred

#> Pontiac Firebird 19.2 17.829311 16.12641 17.20188 17.52899

#> Fiat X1-9 27.3 28.902655 27.72686 28.35547 28.88586

#> Porsche 914-2 26.0 31.136052 28.00826 29.60271 31.41857

#> Lotus Europa 30.4 27.691995 27.01435 27.25625 27.96911

#> Ford Pantera L 15.8 24.928066 19.23691 22.15912 24.89406

#> Ferrari Dino 19.7 16.325756 19.08362 17.23060 16.33122

#> Maserati Bora 15.0 9.759043 12.21058 10.68292 10.48615

#> Volvo 142E 21.4 25.508611 24.96332 25.32522 26.32918

Based on the results that can be seen in the model that produces the closest prediction value y_actual is the Ridge Regression model.

Based on the comparison of the Error values from the models, it was found that the Ridge Regression model which has the smallest Mean Square Error (MSE).

Conclusion

Based on the description above, the following conclusions are obtained:

Multicollinearity problems in the Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression model will make the predictor estimator have a large variance, causing overfitting problems.

Ridge and LASSO regression are good enough to be applied as an alternative if our Ordinary Least Square (OLS) model has multicollinearity problems.

Ridge and LASSO regression work by adding the bias parameter (λ) so that the estimator variance is reduced.

Ridge and LASSO Regression is that if ridge regression can shrink the coefficient close to 0 so that all predictor variables are retained.

LASSO Regression can shrink the coefficient to exactly 0, so that LASSO can select and discard the predictor variables.

Ridge Regression is best used if the data do not have many predictor variables, whereas LASSO Regression is good if the data has many predictor variables, because it will simplify the interpretation of the model.

From the comparison of the above models between OLS Regression, Stepwise Regression, Ridge Regression, and LASSO Regression, the best model is Ridge Regression. Based on the MSE value of the smallest model and the closest prediction estimator to the actual value.

Annotations

Shenoy, Aditi, 2019, What is Bias, Variance and Bias-Variance Tradeoff? (Part 1), viewed 2019, https://aditishenoy.github.io/what-is-bias-variance-and-bias-variance-tradeoff-part-1/

bbroto06, Predicting Labour Wages using Ridge and Lasso Regression, viewed 2019, http://rpubs.com/bbroto06/ridge_lasso_regression

Vidhya, Analytics , 2019, A comprehensive beginners guide for Linear, Ridge and Lasso Regression in Python and R, viewed 2019, https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2017/06/a-comprehensive-guide-for-linear-ridge-and-lasso-regression/

More details

More details More details

More details

Share this post

Twitter

Facebook

LinkedIn